NOOR MUQADAM’S CASE & DIGITAL MEDIA EVIDENCE’S ADMISSIBILITY AS A PRIMARY EVIDENCE.

Introduction

All aspects of human life have evolved due to the change in technology and the justice administration is not left behind. Digital media evidences have come to be one of the most important and in the majority of cases conclusive in the criminal justice systems in the world today. A very recent and high-profile case of Noor Mukadam Murder in Pakistan brought out the role of digital evidence, especially use CCTV footage and forensic reports, in bringing the truth and justice onto the table.

This paper is a critical reflection of the use of digital evidence in contemporary criminal trials, and more specifically its legal framework as defined in the Qanun-e-Shahadat Order, 1984, its amendment to date and how such a practice complies with those of other countries.

Noor Mukadam Case: A Short Review

On 20 July 2021, Noor Mukadam, an Islamabad-based young woman was brutally murdered in the house of Zahir Zakir Jaffer. It created fury nationwide not just because of the ugly nature of the crime in question but also because of the social standing of the perpetrator. In the first instance, the digital evidence became the focus of the case against the defense. The testimonies of CCTV footage of the residence of the accused, forensic reports, DNA reports and the mobile phone records all proved useful in proving the guilt of the accused.

However, there were no direct eyewitnesses and therefore the case depended heavily on circumstantial evidence and the case depended on the authenticity and admissibility of digital evidence. In this decision of the Supreme Court of Pakistan, the concept of using digital evidence as the main and trusted evidence was justified as an essential precedent in the future trials.

Understanding digital evidence.

There is no specific definition of the concept of digital evidence within the Pakistani legislations. But these are coincident terms like: electronic evidence or electronic; which is dealt with under different laws.

The Prevention of Electronic Crimes Act, 2016 (PECA) does define electronic evidence, but mention documents, elements and information that are gathered in electronic mode with reference to an offence (Section 39(1)) . Even the word electronic has a broad definition in PECA (Section 2(g)) to include electrical, digital, magnetic, optical, biometric, electrochemical, electromechanical, wireless or electromagnetic technology

Admissibility of electronic or digital evidence is covered by the Qanoon-e-Shahadat Order (QSO) 1984 especially Article 164 and also on point 46-A. Article 46-A takes note of the admissibility of digital evidence or an evidence obtained in a process involving the use of machines; and Article 164 is acceptable by it.

The QSO was further amended by the Electronic Transactions Ordinance (ETO) 2002 which declared digital evidence as primary evidence and objection to its admissibility based only on the fact that it is digital was removed. Digital evidence is any information that has probative value stored or transmitted in digital form. This contains among others:

- CCTV footage

- Information of computer and cell phones

- Track records are obtained through GPS locations

- Communications on social media

- Recordings in audio and video forms

- Digital photographs

Digital evidence has the advantage that it can be used to make real-time documents that can be indisputable most times. But it can only be used and believed depending upon how well it is taken, and verified according to the statutes.

Qanun-e-Shahadat Order, 1984: digital evidence

The main law which deals with the admissibility of evidence in Pakistan is the Qanun-e-Shahadat Order, 1984 (QSO). Traditionally, the QSO was mainly to cover the traditional varieties of evidence including oral testimony and physical exhibits. Digital evidence, having appeared as a result of modern technological advances, was approached with certain caution and initially considered as a secondary evidence, or even a hearsay.

Article 164 of the QSO permitted the use of evidence collected with modern apparatus in court, however, the wording was ambiguous like the status of digital evidence is a primary or secondary evidence in the case. This legal gray area placed obstacles on prosecutors and the court in enabling the efficient use of digital evidence.

Changes to QSO and its Effects

The Pakistani legislature had noticed an increasing significance of digital evidence and made huge amendments to the Electronic Transactions Ordinance, 2002, and the Criminal Law (Amendment) Acts of 2017 and 2023.

The important Amendments are as follows:

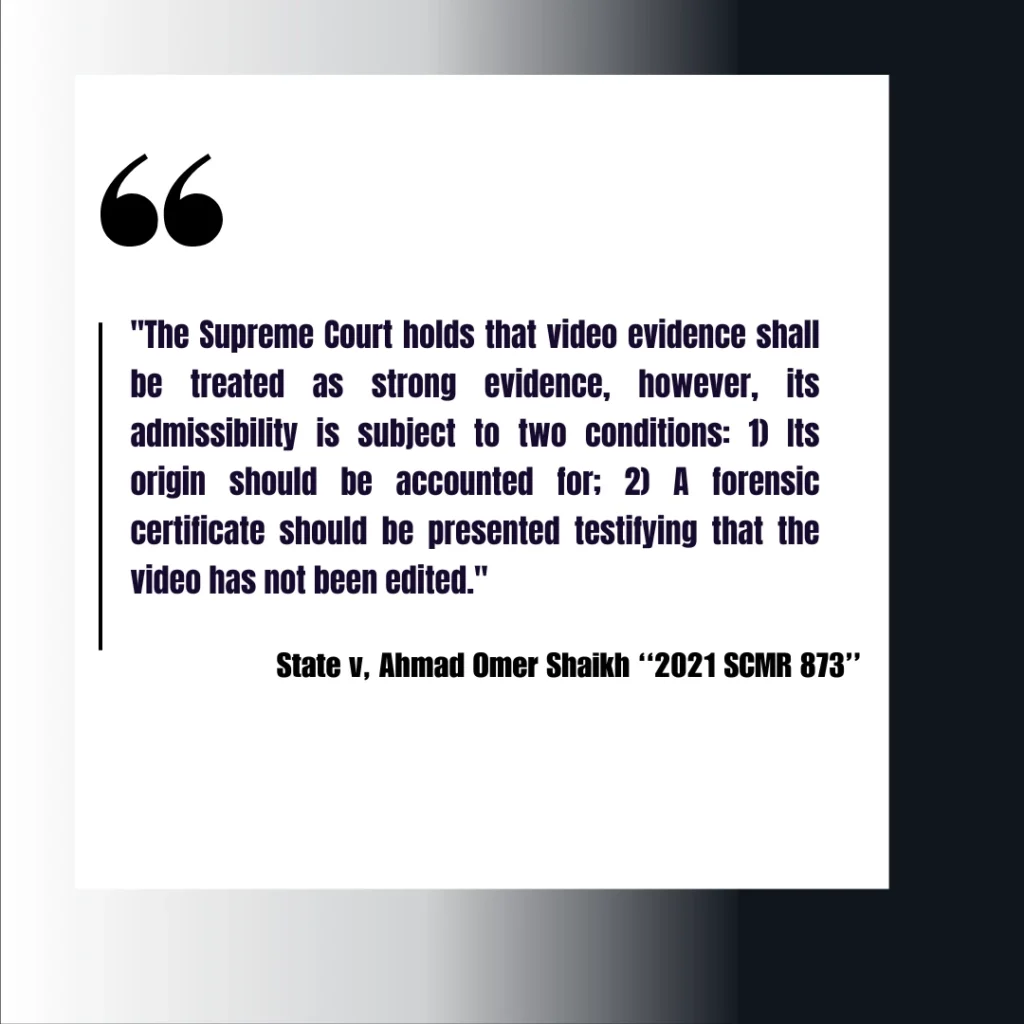

The terms used in article 2(e), 73 (explanation3, and 4), 46-A and article 164 of the QSO have now included the other terms like electronic document, information system, security procedure which are as specified in the electronic transactions ordinance 2002. And the further, it was elaborate in the decision honorable Supreme court of Pakistan in the case of state v. Ahmad Omar Shaikh “2021 SCMR 873” in which the 2-step verification process was introduced to ensure the authenticity.

Main position of digital evidence:

Article 73 explanation 3 and 4 make it clear that printouts or an output of an automated information system is considered to be a primary evidence when the system was functional.

- Explanation 3: [Explanation 3.—A printout or other form of output of an automated information system shall not be denied the status of primary evidence solely for the reason that it was generated, sent, received or stored in electronic form if the automated information system was in working order at all material times and, for the purposes hereof, in the absence of evidence to the contrary, it shall be presumed that the automated information system was in working order at all material times.

- Explanation 4: —A printout or other form of reproduction of an electronic documents, other than a document mentioned in Explanation 3 above, first generated, sent, received or stored in electronic form, shall be treated as primary evidence where a security procedure was applied thereto at the time it was generated, sent, received or stored.]

In the Qanoon-e-Shahadat Order 1984, such evidence may be termed as the Primary evidence to the court is exhibited the primary document itself (Article 73). But in order to embrace the digital age, Explanation 3 goes ahead to explain that print out or output of a computer system (say an email or an online bank statement) can also be taken as primary evidence in the event that the system was functioning properly in which the law assumed that the system was functional unless the contrary was established.

Beyond that, Explanation 4 extends this to other types of electronic documents whose printouts can be taken as direct evidence in case a certain “security procedure” (such as digital signature or encryption) was used to create the document, or to store it, guaranteeing both authenticity and integrity.

Article 46-A directly acknowledges procedures of automated information systems generating, receiving or recording information as the facts concerned.

- [46-A. Relevance of information generated, received or recorded by automated information system. — Statements in the form of electronic documents generated, received or recorded by an automated information system while it is in working order, are relevant facts.]

When computer system or some other automatized systems (e.g., Computers (laptops, desktops, servers) Smartphones ATMs, Security cameras with digital recording, Electronic sensors (e.g., in factories or vehicles), Software programs a smart device or a machine that automatically kept records) either creates any information (including an electronic signature, emails, digital transactions, data from GPS devices and even text messages ), or it receives or stores, then any such information may be used in courts as relevant evidence, as long as the system was functioning properly at the time it generated or processed such information.

Article 164 as amended in 2023:

The amended section permits the use of evidence or statement of witnesses’ recording by the modern technology suchlike video call, WhatsApp, Skype, et cetera, depending on the character and the situation of the case.

According to article 164 of the Qanoon-e-Shahadat Order in Pakistan, 1984, the court may admit such evidence or take witness etc. which is obtained by using modern technologies such as video calls (e.g. Skype, WhatsApp) and video conferencing, as long as this is considered suitable based on nature and circumstances of the case at hand. These provisions allow the judiciary to use modern digital technologies to simplify legal proceedings and collect information in the most efficient way, e. g. a witness based in another country can testify through a video channel.

The silent witness theory:

The Silent Witness Theory is a legal principle according to which photographs, videos, or any other available recording that contains direct information can be used as direct, substantive evidence without the need to validating the given events through an eyewitness, but only as long as the integrity and authenticity of the recording of the given occurrence is proved.

The theory will be especially applicable when there was no human observer to the said events but proper technology documented it. This principle is used in courts to allow digital recordings to be used as the silent witnesses to the events because the events would then speak up.

The Supreme Court of Pakistan specifically used the Silent Witness Theory in Noor Mukadam case. The CCTV recordings in the house of the accused came out as the deciding evidence. Confirmed by forensic experts as not a tampered footage, some of the key parts of th footage showed the victim trying to escape, being forcefully shoved down by the accused and finally being pulled back inside the house. This was the final photographic evidence of the survivor when she was alive.

Being based on forensic reports and focusing on the provisions set out in the case law at the international level, the Supreme Court was able to recognize the CCTV video as the first, substantial evidence by means of the Silent Witness Theory. Particularly, the Court referred to the case of State v. Ahmed Omar Sheikh (2021 SCMR 873) which established two prong test that should be met to admit digital evidence; (i) establish the source and chain of custody and (ii) there is forensic verification of the integrity of recordings.

By applying the Silent Witness Theory, the Court avoided considering direct account on the part of human beings on what really occurred in the event but trusted the real-time record which was objectively captured by technology. Such a strategy did not only solidify the case of the prosecution, but also highlighted the growing dependency on technology-based evidence within criminal justice system in Pakistan.

Criteria for the Admissibility of the Digital Evidence precisely Audio and Video Evidences

These are the rules to establish an audio or a video in the Court. was expounded in the matter of Ishtiaq Ahmed Mirza and others v. Federation of Pakistan (PLD 2019 SC 675). After referring courts have made many rulings regarding the point on the following lines:

- No audio tape or video can be relied upon by a court until the same is proved to be genuine and not tampered with or doctored.

- A forensic report prepared by an analyst of the Punjab Forensic Science Agency in respect of an audio tape or video is per se admissible in evidence in view of the provisions of section 9(3) of the Punjab Forensic Science Agency Act, 2007.

- Under Article 164 of the Qanun-e-Shahadat Order, 1984 it lies in the discretion of a court to allow any evidence becoming available through an audio tape or video to be produced.

- Even where a court allows an audio tape or video to be produced in evidence such audio tape or video has to be proved in accordance with the law of evidence.

- Accuracy of the recording must be proved and satisfactory evidence, direct or circumstantial, has to be produced so as to rule out any possibility of tampering with the record.

- An audio tape or video sought to be produced in evidence must be the actual record of the conversation as and when it was made or of the event as and when it took place.

- The person recording the conversation or event has to be produced.

- The person recording the conversation or event must produce the audio tape or video himself.

The audio tape or video must be played in the court. - An audio tape or video produced before a court as evidence ought to be clearly audible or viewable.

- The person recording the conversation or event must identify the voice of the person speaking or the person seen or the voice or person seen may be identified by any other person who recognizes such voice or person.

- Any other person present at the time of making of the conversation or taking place of the event may also testify in support of the conversation heard in the audio tape or the event shown in the video.

The voices recorded or the persons shown must be properly identified. - The evidence sought to be produced through an audio tape or video has to be relevant to the controversy and otherwise admissible.

- Safe custody of the audio tape or video after its preparation till production before the court must be proved.

- The transcript of the audio tape or video must have been prepared under independent supervision and control.

- The person recording an audio tape or video may be a person whose part of routine duties is recording of an audio tape or video and he should not be a person who has recorded the audio tape or video for the purpose of laying a trap to procure evidence.

- The source of an audio tape or video becoming available has to be disclosed.

The date of acquiring the audio tape or video by the person producing it before the court ought to be disclosed by such person. - An audio tape or video produced at a late stage of a judicial proceeding may be looked at with suspicion.

- A formal application has to be filed before the court by the person desiring an audio tape or video to be brought on the record of the case as evidence.”

The Use of Digital Evidence in International Jurisdictions

The question of admissibility and the use of the digital evidence is not peculiar to Pakistan. Digital evidence has not only gained acceptance by the courts worldwide, but it has also been viewed rather positively due to its credibility, at least to the extent that it can satisfy the attribute of authenticity and integrity.

United States: The silence witness theory is well substantiated and therefore photography, video recordings, or video tapes can be used as real evidence without someone having to confirm the events that have been recorded, it can be presented as real evidence. Such landmark cases as the United States v. United States v.Taylor (1976) and United States Rembert (1988) have also supported the admissibility of digital evidence on the basis of reliability of the system and forensic examination.

United Kingdom: Similar principles are applicable in British courts where they concentrate on the integrity of the record. R v. Atkin (2009) and R V. As confirmed by Gubinas (2017), CCTV footage was admitted as primary evidence after the authenticity of the same.

Canada: In R v., the Canadian Supreme Court noted that the Maple. Nikolovski (1996) understood that even in cases where there are no direct eyewitnesses, high-quality video evidence has the potential to spell the difference in convicting the accused persons.

India: The Indian courts have also shifted to utilizing more of the digital evidence and especially since the amendment of Indian Evidence Act, 1872 to accommodate the electronic records as admissible.

Critical Analysis: Opportunities, and Changes

Opportunities:

It has been observed that the apparition of digital evidence in criminal justice systems has certain great benefits. The first is that it enhances the prowess of crime solving to a greater degree leaving less room to error when crime is to be solved. In addition, it reduces the use of human witnesses who might have lapses in memory, are afraid or can be influenced. Instant recording of incidents via CCTV, mobile recording and use of the GPS system offers decent, time-stamped records of events. Moreover, incorporation of digital evidence has greatly enhanced forensics and method of investigation giving rise to a more scientific, and evidence based prosecution and defense.

Challenges:

However, although these are some of the advantages associated with digital evidence, there are also significant challenges to digital evidence. The top issue that can challenge the integrity of digital data is the chances of interference, tampering, or alteration of data. This raises the requirement of superior and safe forensic mechanisms to ensure authentication.

Moreover, the lack of high-tech in forensics skills is an added pressure to the developing countries that have low resources. Privacy issues also abound where the increased surveillance technology has challenged the rights of the individuals as opposed to the security of the state. Last but not least, one cannot overlook the possibility of misuse of digital evidence by powerful individuals or state machinery due to selective disclosure of the digital evidence or its manipulation in order to skew justice.

The case of Noor Mukadam demonstrates the possibilities, as well as deficiencies of digital evidence. The involvement of the suspect was proved beyond any doubt through CCTVs and forensic reports. Nonetheless, some lamentations regarding media trials, government interference, and bias in the presentation of evidence all tell us that although the digital tools would help in the improvement of any justice system, they should be applied in an open and fair manner.

Conclusion

The importance of digital evidence in criminal justice system today is arguably huge. The legal reforms undertaken by Pakistan and especially the amendments to the Qanun-e-Shahadat Order, 1984 is a fundamental step in the direction of adopting the use of technology in the name of justice. But to make the electronic evidence an effective foundation of justice, the gathering, storing and using of it should follow the rules of the law and the technology closely.

To move on, Pakistan needs to invest in its own capacity building of forensic experts, judicial officers who work with such evidence should be well trained and strict measures against manipulating data should be applied. There is a lot to learn in terms of striking the right balance between innovation in technology and safeguarding basic rights through international best practices as evidenced in the United States, UK, Canada and India.

Although very tragic, the case of Noor Mukadam has spearheaded important debates relating to the development of law on evidence jurisprudence in Pakistan. It is to remind us that as much as technology can be the means to the end concerning bringing people to justice, its use or contravention can as well be the hindering factor to the same. Therefore, the thoughtful inclusion of technological evidence in the just and transparent legal policy is what is needed to maintain digital justice.